Introduction

In financial reporting, understanding how to reverse an impairment for a Cash-Generating Unit (CGU) under IFRS is important for keeping financial statements accurate. Impairment reversal means checking if a previous write-down of an asset’s value should be adjusted because things have improved. This could happen if market conditions get better, technology advances, or the asset is used more effectively. However, there are rules to follow: the reversal can’t make the asset’s value higher than it originally was, and you can’t reverse impairments on goodwill. This article will explain and illustrate the key principles behind CGU impairment reversal and how it affects a company’s financial statements.

Indicators of impairment reversal

The key IFRS guidance that deals with the topic of impairment reversal indicators is IAS 36, and in particular, the section 111:

In assessing whether there is any indication that an impairment loss recognised in prior periods for an asset other than goodwill may no longer exist or may have decreased, an entity shall consider, as a minimum, the following indications:

External sources of information

(a) there are observable indications that the asset’s value has increased significantly during the period.

(b) significant changes with a favourable effect on the entity have taken place during the period, or will take place in the near future, in the technological, market, economic or legal environment in which the entity operates or in the market to which the asset is dedicated.

(c) market interest rates or other market rates of return on investments have decreased during the period, and those decreases are likely to affect the discount rate used in calculating the asset’s value in use and increase the asset’s recoverable amount materially.

Internal sources of information

(d) significant changes with a favourable effect on the entity have taken place during the period, or are expected to take place in the near future, in the extent to which, or manner in which, the asset is used or is expected to be used. These changes include costs incurred during the period to improve or enhance the asset’s performance or restructure the operation to which the asset belongs.

(e) evidence is available from internal reporting that indicates that the economic performance of the asset is, or will be, better than expected.

Relevant accounting guidance

The overall principles for assessing and recording impairment reversal for a cash generating unit are set out by IAS 36, sections 122-125. In particular, the section emphasizes ceiling for reversal, that asset can only be written up to the lower of its recoverable amount and carrying amount that would have been recognized had the impairment not occurred, and that goodwill impairment is irreversible.

A reversal of an impairment loss for a cash-generating unit shall be allocated to the assets of the unit, except for goodwill, pro rata with the carrying amounts of those assets. These increases in carrying amounts shall be treated as reversals of impairment losses for individual assets and recognised in accordance with paragraph 119.

In allocating a reversal of an impairment loss for a cash-generating unit in accordance with paragraph 122, the carrying amount of an asset shall not be increased above the lower of:

(a) its recoverable amount (if determinable); and

(b) the carrying amount that would have been determined (net of amortisation or depreciation) had no impairment loss been recognised for the asset in prior periods.

The amount of the reversal of the impairment loss that would otherwise have been allocated to the asset shall be allocated pro rata to the other assets of the unit, except for goodwill.

Reversing an impairment loss for goodwill

An impairment loss recognised for goodwill shall not be reversed in a subsequent period. IAS 38 Intangible Assets prohibits the recognition of internally generated goodwill. Any increase in the recoverable amount of goodwill in the periods following the recognition of an impairment loss for that goodwill is likely to be an increase in internally generated goodwill, rather than a reversal of the impairment loss recognised for the acquired goodwill.

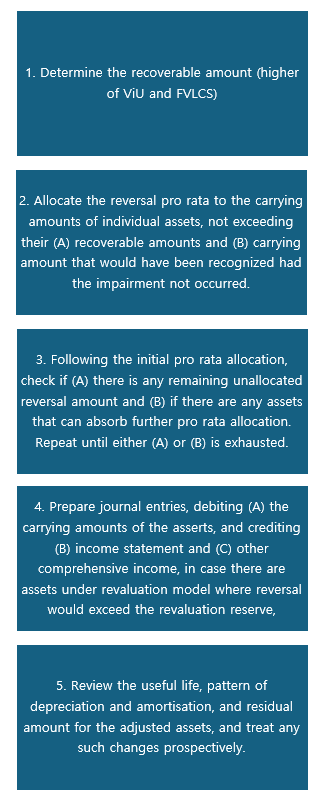

Summary of the process

Below is a summary of the process that can be followed by an accountant.

Illustrative example

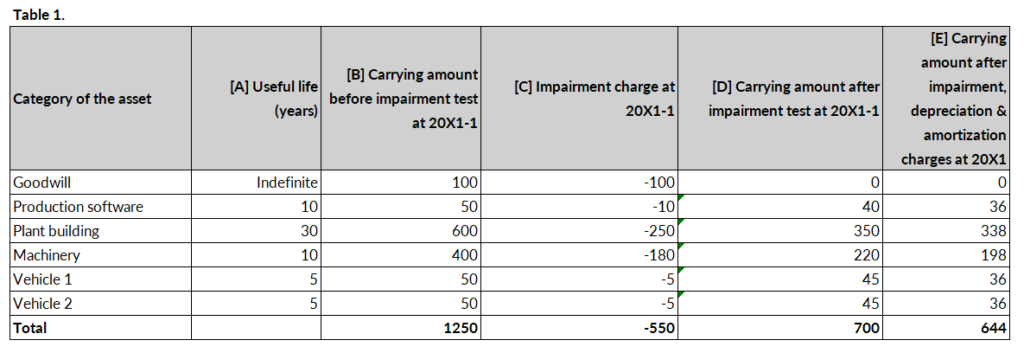

Below is an illustrative example of a manufacturing company that did initially recognize an impairment of its key CGU, but in a subsequent year, due to sustainable improvement in the business performance performed a valuation exercise and concluded that the impairment booked in the previous period should be reversed.

The table below shows the original parameters of the assets allocated to the key CGU, their carrying amounts, and then calculated impairment that was booked in the previous period, as well as subsequent depreciation & amortization.

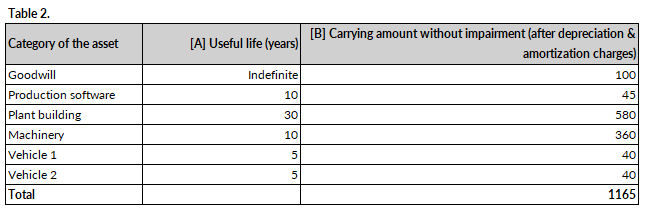

The table below shows would-be values if impairment never occurred. The amounts serve here as an input for determination of ceiling values.

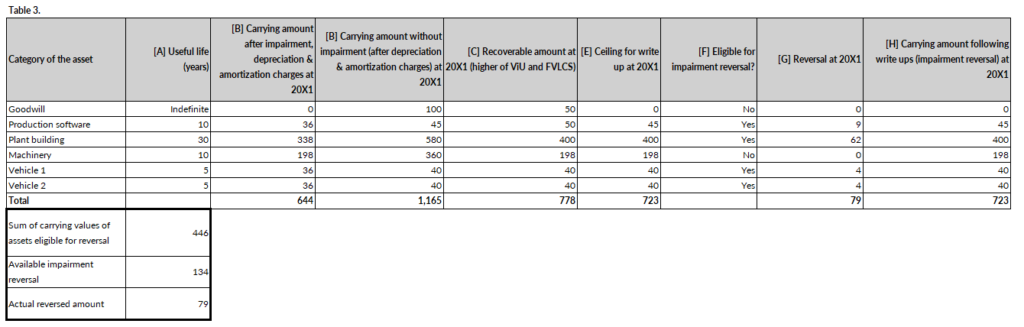

This table shows a calculation of impairment reversal at 20X1. It is illustrated how impairment reversal would look like. The key principle is that the available impairment reversal is pro rata allocated only to the eligible assets. Hence the formula for allocation is [carrying amount of a given eligible asset / SUM of carrying values of all eligible assets X available impairment reversal]. The process is iterated until either all assets reach their ceiling level or there is no available impairment reversal left that can be allocated. The values in column [H] are post impairment reversal. The impairment reversal amount of 79 remains unallocated, given that the revised asset values for each asset have already reached either their possible revised carrying amount or recoverable amount.

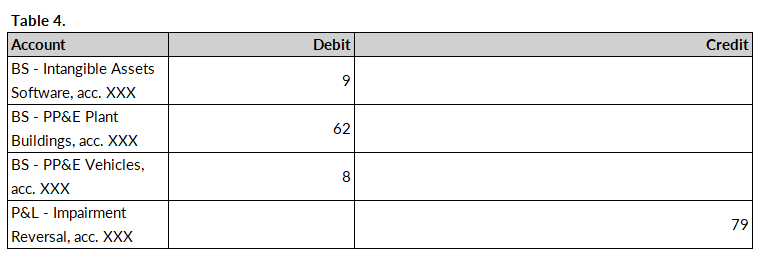

The table below shows a journal entry for impairment reversal.

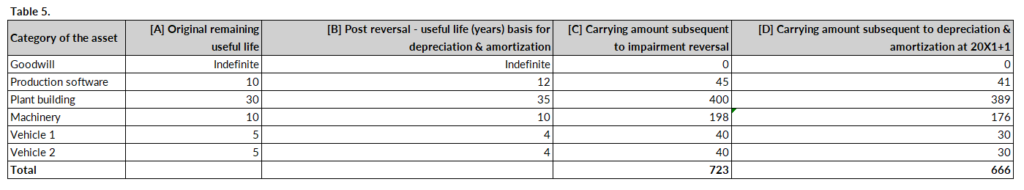

Below is illustrated a subsequent accounting at 20X1+1, as well as the journal entry. IFRS indicates that upon impairment reversal it should be assessed whether there should be changes to remaining useful life, depreciation method, or the residual value (IAS 36.113). In this example below, we can assume that useful life of “Production software” and “Plant building” has been revised upwards. As for Machinery, this remains based on the original 10 years. Any changes should be accounted for prospectively, and the resulting calculation would look as follows.

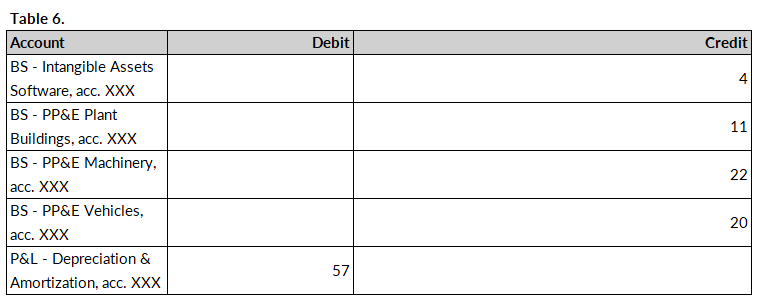

The journal entry would be as follows:

Excel file attachment

The attached file contains the tables and the relevant formulas.

Conclusion

The post above illustrated how to calculate and book an impairment reversal in practice in accordance with IAS 36 requirements.